Learning an Indigenous language through tech and the new normal

Gii wiijiiye Anishinaabemowin Zoom akinoomaageng.

Try saying this phrase. Here’s how it’s pronounced.

GEE WEE-JEE-YA AH-NISH-AH-NAH-BAY-MOW-IN ZOOM AH-KE-NOO-MAH-GAYNG.

You just said, “I attended an Anishinaabe language Zoom class.”

Zooming your way through language classes

During the global pandemic, many people have been able to put time into things they didn’t have time for before. And some are taking to learning a traditional Indigenous language. Through modern tools like videoconferencing and online classes, this is possible even in the new normal of social distancing.

This learning is so important, since Indigenous languages throughout the world are endangered. In fact, the world’s linguistic diversity is also under threat — with 96 per cent of the world’s 6,700 languages spoken by only three per cent of the peoples.

Over half of these languages (around four-thousand) are actually Indigenous languages. As widely spoken languages such as English, Spanish and Mandarin continue to be favoured, we see other languages fade away. Sadly, one Indigenous language “dies” per week.

Also read: How the Indigenous Leadership Circle is providing leadership in Reconciliation

Why Indigenous languages must survive

A language, of course, doesn’t die – the people who use it do.

In Canada, 87 Indigenous languages exist, and this number is rapidly shrinking. Due to residential schools and other policies that have marginalized Indigenous cultures, refusing to recognize them on par with English and French, there are now too few young speakers remaining. In addition, there is a lack of infrastructure to keep these languages alive and in full use through to future generations.

Yet, Indigenous languages have critical value. They are the oldest and richest languages on this continent, with words and phrases that describe, document and demonstrate the histories, ways of life and stories of this place.

While other languages do some of this, too, none do it to the same degree. Indigenous languages also describe our home, tell us how to live in the best way possible and embed people in relationships with the land, water and non-human beings in sustainable and positive ways. One only has to know the meaning of the terms Winnipec, Manitowapow and Kanata to know what I mean.

Technology makes it easier to learn

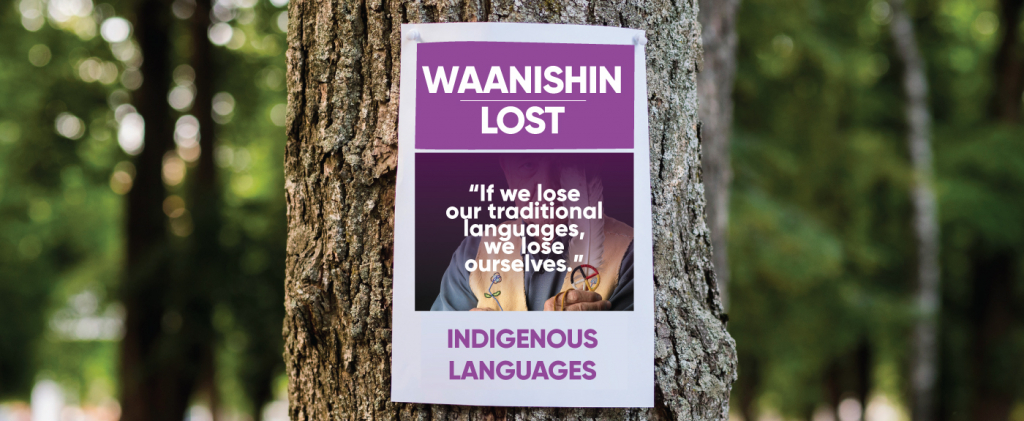

Saving Indigenous languages is about saving our collective history, knowledge and experience. This is why many elders say: “If we lose our traditional languages, we lose ourselves.”

So now – more than ever in history – people are working overtime to save Indigenous languages. New books and dictionaries are being created. Language nests and culture camps are popping up continually. Many resources are being developed on websites, through phone apps and other online language programming such as Facebook Live, YouTube and even TikTok. Through this modern technology, you can find grandmothers showing how to bead in Cree or medicine keepers teaching how to pick bear root in Blackfoot.

Did I mention all of these are free?

Over recent months, new programming is appearing and gaining new audiences due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many are teaching pandemic-specific lessons, like “to be prepared” and “wash your hands.”

By the way: that’s “Ashowizon” (ASH-O-WAH-ZON) and “Gii ziibiiginan jiin” (GEE ZEE-BEE-GA-NAAN JIN).

There’s more Indigenous words that can help us through this time. The word for headache is “dekwewin” (DAH-KWAY-WIN), phlegm is “skwaajigewin” (SKAH-WAH-JE-GA-WIN) and sore throat is “gaagiijigondaaginewin” (GAA-GEE-JA-GOON-DAA-GI-NAY-WIN).

COVID-19 is GOOBID-19 (hope you don’t need pronunciation for that one).

Case study: Learning Ojibway

At ACU and throughout Manitoba, people are working hard to learn the language regardless of this stressful time. For example, Financial Service Advisor, Kirstin Witwicki, has been working hard to learn Ojibway, the language of her grandmother.

As she explains, every word she learns brings her closer to her grandmother.

“For me, learning the language is important because my granny worked so hard to retain it against all odds,” Kirstin says. “Her strength and resilience at such a young age is inspiring. If she loved her language enough to keep it throughout her many years spent in the residential school, then the least I can do it is try to love it just as much. She passed away in 2008, but every time I speak a word in Anishanaabemowin, it brings me a little closer to her memory — and I can almost hear her voice.”

At the same time, learning to speak Ojibway is a “struggle,” Witwicki explains. It takes time and effort, but results in “that moment of joy when you string together a sentence that makes just enough sense that another person can understand you.” This is the feeling that keeps you going forward.

“It also brings me a lot of happiness when I hear someone speak the language, and I can actually understand what they’re saying. And seeing someone overcome their anxiety of speaking it out loud and gaining confidence is heartwarming to watch.”

Related: ACU Employee Spotlight: Getting to know Kirstin Witwicki

Indigenous languages have the power to heal

These days, more and more online classes offer advanced teachings in verb use and spiritual teachings, addressing the main challenge with online learning: inspiring fluency. Online programming may not lead to many fluent speakers (immersion programs do this better), however, this intersection of technology and Indigenous languages is a ray of hope for language advocates.

As Kirstin demonstrates, Indigenous language learning is also part of healing and addresses challenges in Indigenous communities – such as youth suicide. Learning an Indigenous language connects communities and supports youth to obtain a better sense of self-worth and identity. Want a cure for cultural shame? How about low graduation rates? Gangs or crime? Language programming is where these solutions begin.

So, let’s all make attempts to help learn and save Indigenous languages.

Gii daagshkitoon gwa! You can do it.

Up Next

Sustainability: How ACU is turning words into action

A hand holding a seedling

For ACU, Pride radiates outward

“I’ve always wanted to instill a change in the world for the better,” says Cristina McCourt, Financial Account Manager Trainee and member of the ACU Pride Committee, an employee-led resource…

Royal Aviation Museum travels to its final destination—with ACU’s help

A stone’s throw from the main terminal of Winnipeg Richardson International Airport you’ll find one of Canada’s hidden gems, where the airplanes are a little more exciting than your typical…