Posted: August 09, 2022 by Asterisk Blog in Community stories, Dene, Endangered Languages Project, Honouring our Languages Conference, Indigenous languages, Indigenous Languages Act, Indigenous Languages of Manitoba, language preservation, Los Pinos Declaration, Manitoba Metis Federation, Métis, Michif, MMF, Ojibway, Reconciliation, UNESCO, United Nations

Big deal. So what if a few Indigenous languages are lost?

As a teenager, like most, ACU Brand & Campaign Specialist Lisa Delorme Meiler did not listen to her Elders when it came to language preservation.

“I grew up francophone, and I remember my mémère (grandmother), who also was a French Immersion school teacher, saying to me, don’t lose your language! She would only speak French in her home and we, too, were expected to do the same,” Lisa reflected. “At school, it was cool to speak English with my friends, so little by little, I used French less and less.”

“As a result of those actions, if I try to speak French today I can barely carry on a full conversation and often default to “Franglais.” For the most part, I can understand French, but my ability to write is very poor,” she said. “I wish I would’ve listened to my mémère’s wise words back then. I finally get it.”

Unfortunately, Lisa’s experience isn’t unique and is part of a broader conversation on the importance of language preservation, particularly within Indigenous communities.

Losing our languages

Every day, many Indigenous languages inch closer to extinction. According to UNESCO, “at least 40% of the 7,000 languages used worldwide are at some level of endangerment.”

In Canada, there are 73 Indigenous languages that are endangered or could become extinct, some with less than 500 persons who can fluently speak their languages. Some of these critically endangered Indigenous languages include those spoken in the Prairies such as the Assiniboine language (also known as Assiniboin, Hohe, or Nakota, Nakoda, Nakon, or Nakona, or Stoney), which is a Nakotan Siouan language of the Northern Plains.

While reliable figures are hard to come by, experts agree that Indigenous languages are particularly vulnerable because many of them are not taught at school or used in public spaces. Indigenous languages are key to social cohesion and inclusion, cultural rights, health and justice. They form identity, create language biodiversity and connect us to ancient and traditional knowledge that binds humanity with nature and our culture.

Reclaiming Indigenous languages is also an important aspect of reconciliation. It is a fundamental step toward people feeling connected to their culture and community.

Indigenous language in danger of extinction

Below are just some of the 73 Indigenous languages that are considered endangered. For the complete list, visit the Endangered Languages Project.

- The Assiniboine language (also known as Assiniboin, Hohe, or Nakota, Nakoda, Nakon, or Nakona, or Stoney) is a Nakotan Siouan language of the Northern Plains.

- Bungi /?b?n.?i/ (also called Bungee, Bungie, Bungay, Bangay, or the Red River Dialect) is a dialect of English with substantial influence from Scottish English, the Orcadian dialect of Scots, Norn, Scottish Gaelic, French, Cree, and Ojibwe (Saulteaux)

- Cayuga (Cayuga: Gayogo?hó?n??) is a Northern Iroquoian language of the Iroquois Proper (also known as “Five Nations Iroquois”) subfamily, and is spoken in the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation, Ontario, by around 240 Cayuga people, and on the Cattaraugus Reservation, New York, by fewer than 10.

- Comox is a Coast Salish language historically spoken in the northern Georgia Strait region, spanning the east coast of Vancouver Island and the northern Sunshine Coast and adjoining inlets and islands.

- Dakota (Dakhótiyapi, Dak?ótiyapi), also referred to as Dakhota, is a Siouan language spoken by the Dakota people of the Sioux tribes.

- The Haisla language, X?a’islak?ala or X?àh?isl?ak?ala, is a First Nations language spoken by the Haisla people of the North Coast region of the Canadian province of British Columbia, who is based in the village of Kitamaat.

- Halkomelem (/h?lk??me?l?m/; Halq?eméylem in the Upriver dialect, Hul?q?umín?um? in the Island dialect, and h?n?q??min??m? in the Downriver dialect) is a language of various First Nations peoples of the British Columbia Coast.

- The Hän language (alternatively spelled as Haen) (also known as Dawson, Han-Kutchin, Moosehide; ISO 639-3 haa) is a Northern Athabaskan language spoken by the Hän Hwëch’in (translated to people who live along the river, sometimes anglicized as Hankutchin).

- Heiltsuk /?he?lts?k/, also known as Haí?zaqv,

- Bella Bella and Haihais, is a dialect of the North Wakashan (Kwakiutlan) language Heiltsuk-Oowekyala that is spoken by the Haihai (Xai’xais) and Bella Bella First Nations peoples of the Central Coast region of the Canadian province of British Columbia, around the communities of Bella Bella and Klemtu, British Columbia.

- Inuit Sign Language (IUR, Inuktitut: Uukturausingit or Atgangmuurngniq) is an indigenous sign language. It is a language isolated native to Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic.

- Kwak?wala (/kw???kw??l?/), or Kwak?wala, previously known as Kwakiutl (/?kw??kj?t?l/),is the Indigenous language spoken by the Kwakwaka?wakw (which means “those who speak Kwak?wala”) in Western Canada.Kwak?wala (/kw???kw??l?/), or Kwak?wala, previously known as Kwakiutl (/?kw??kj?t?l/), is the Indigenous language spoken by the Kwakwaka?wakw (which means “those who speak Kwak?wala”) in Western Canada.

- Lakota (Lak?ótiyapi [la.?k??.t?.ja.p?]), also referred to as Lakhota, Teton, or Teton Sioux is a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota people of the Sioux tribes.

- Munsee (also known as Munsee Delaware, Delaware, Ontario Delaware, Delaware: Huluníixsuwaakan, Monsii èlixsuwakàn) is an endangered language of the Eastern Algonquian subgroup of the Algonquian language family, itself a branch of the Algic language family.

- Haida /?ha?d?/ (X?aat Kíl, X?aadas Kíl, X?aayda Kil, Xaad kil) is the language of the Haida people, spoken in the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the coast of Canada and on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska.Nuxalk /?nu?h?lk/, also known as Bella Coola /?b?l?.?ku?l?/, is a Salishan language spoken by the Nuxalk people. Today, it is an endangered language with only 3 fluent speakers in the vicinity of the Canadian town of Bella Coola, British Columbia.

- Inuktitut (/??n?kt?t?t/; Inuktitut: [inukti?tut], syllabics; from inuk, “person” + -titut, “like”, “in the manner of”), also Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada.

- Michif (also Mitchif, Mechif, Michif-Cree, Métif, Métchif, or French Cree) is the language of the Métis people of Canada and the United States, who are the descendants of First Nations women (mainly Cree, Nakota, and Ojibwe) and fur trade workers of white ancestry (mainly French and Scottish Canadians).

Get involved: 2022 is the start of a decade of action

In 2020, more than 500 participants from 50 countries, including government ministers, Indigenous leaders, researchers, partners and experts, adopted the Los Pinos Declaration. Framed by the slogan “Nothing for us without us,” UNESCO explains that, “the Declaration places Indigenous Peoples at the centre of its recommendations.”

From that meeting, the United Nations proclaimed 2022 to 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, with the purpose of drawing global attention to the critical status of many Indigenous languages around the world. They also intend to mobilize stakeholders and resources for the preservation of these languages.

In November 2021, a Global Action Plan was also approved as part of this International Decade of Indigenous Languages. It outlines specific goals and expected outcomes for the next 10 years, setting the stage for activities and events focused on the revitalization of Indigenous languages.

The Canadian government is also building on that momentum. Our country will continue to work closely with Indigenous partners to plan specific initiatives and activities to advance the decade’s objectives. This includes implementing the Indigenous Languages Act and creating a National Action Plan recognizing the priorities of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples for their languages.

The less you use it, the more you lose it

As a Red River Métis woman on a journey to reclaim her Métis culture and language, when Lisa saw Michif on the critically endangered list, she was enveloped with emotions.

“I feel ashamed that I don’t know my language of Michif. I remember attending an event through the Manitoba Métis Federation, a kitchen table talk with Elders, and the Elder asked me if I could speak Michif. When I said no, I remember the disappointment on the Elder’s face.”

After that event, Lisa was prompted to visit the Gabriel Dumont Institute site to explore the Michif language, which is a combination of French nouns and Cree verbs. Scrolling through the vocabulary, childhood memories flooded back and she was surprised that she knew some of those words—realizing her fathers’ parents had actually spoken Michif. “I just thought it was broken French as a kid,” Lisa said of her discovery.

For Lisa, the coming decade will be meaningful as part of her journey with her family language. While much has already been lost, she feels there are many new opportunities to preserve Indigenous languages.

We must all do our part to preserve these languages. Many Indigenous women are reclaiming Indigenous matriarchy, leading initiatives to reclaim and revitalize their languages. Looking to our older generations, Elders are the keepers of this knowledge of these languages, and we have much to learn from them. And for all Indigenous Peoples and allies around the globe, it’s a crucial moment to lay solid foundations for Indigenous language preservation so that they can live on for future generations.

Beautiful words spoken

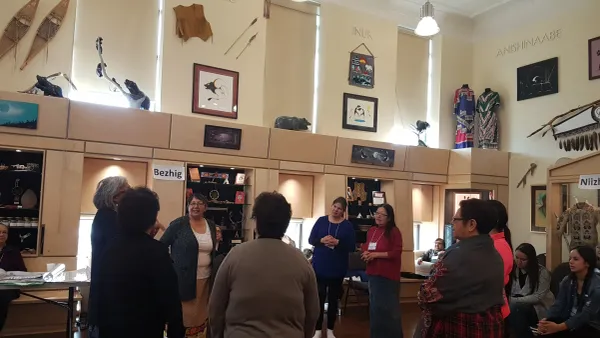

Events close to home are great opportunities to get exposure to different languages. In 2021, Lisa took part in the Honouring our Languages Conference, hosted by Indigenous Languages of Manitoba, a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring the strength and survival of our Indigenous languages. Her experience at the conference was memorable to say the least.

“It was so amazing and beautiful to hear Indigenous Peoples speaking their language. Part of our identity lies in understanding language. So many of the Indigenous cultures are based on oral teachings,” she recounted of the event.

“Truth, I could not understand many of the languages, but it was an absolute honour to hear the participants speak their Indigenous language and to hear the proudly spoken words. I hope to hear more Indigenous speaking in the community in future years.”

The experience of the conference also inspired Lisa to continue her language journey. She wrote her first post on social media in Michif, using a Michif/Cree Dictionary she purchased at the conference. “I’m sure it was full of mistakes, but that’s ok, I’m trying to learn,” Lisa said.

“I’m grateful to all our Elders who are trying to keep our languages alive. I’m grateful to organizations like Indigenous Languages Manitoba, which are teaching future generations to speak Indigenous Languages. Every Indigenous person should have the opportunity to be fluent.”

The joy of reclaiming, promoting and speaking Indigenous languages

While organizations and governments have committed to work on protecting and promoting Indigenous languages, Lisa feels like it is a collective responsibility to commit to learning. And it can be a wonderful experience.

“I’m going to continue learning words and will look at taking language courses. I’ll try to start by introducing myself in Michif. “Ni owîhôwin Lisa Delorme Meiler, ooshchi Ápihtaw kosisân piyako sihtâwin.” My name is Lisa Delorme Meiler, from the Métis Nation.”

She also believes allyship is key in encouraging Indigenous languages survival. “For those whose Indigenous language is not theirs, celebrate people trying to learn and reclaim their language,” she suggests. “Encourage them in their learning journey, and maybe learn a greeting or a word so that Indigenous peoples feel like their language is important. Because it is.“

“We need to normalize Indigenous languages, and we need to make it “cool and hip” to speak your language. We need to remove barriers—whether it be cost or accessibility. And overall, we need to use it, or we’ll lose it.”

Meena kawapimitin.

Up Next

Community stories

Read more ›

Celebrating the 10th anniversary of student-run credit union

Just over 10 years ago, a survey circulated at Winnipeg’s Technical Vocational High School. The results showed that students at the school, commonly known as Tec Voc, felt short-changed—they were…

Borrow, Business growth, Community stories

Read more ›

Kilter Brewing Co. serves up craft beer and community connection in St. Boniface

Deep in the heart of St. Boniface, Kilter Brewing Company is a hidden treasure—an oasis for Winnipeggers to escape their day-to-day routines, enjoy craft beer and connect with their community….

Borrow, General, Money tips

Read more ›

How to use a mortgage calculator to budget better

Learn how to use ACU’s mortgage calculator to figure out how much mortgage you can afford, and what budget you should set before you start house hunting. A mortgage lender…